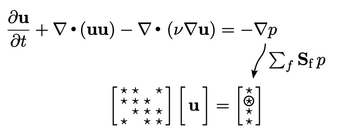

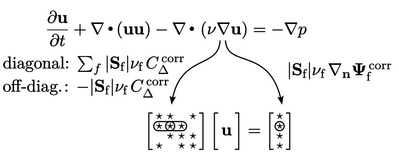

3.24 Example of building a matrix equation

The previous sections describe methods to

discretise derivative and other terms in order to build a matrix

equation for a given physical equation. Let us demonstrate the

construction of a matrix equation, using the momentum conservation

equation from Sec. 3.23

as an example. It is

a vector equation, so produces 3 matrix equations for  ,

,  and

and

.

.

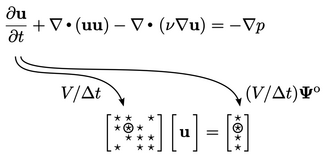

The first term, the time derivative  , might be

discretised with the Euler scheme Eq. (3.21

). Matrix equations are

constructed in extensive

form as discussed in Sec. 3.6

. Hence, the

contributions from Eq. (3.21

) to matrix coefficients

, might be

discretised with the Euler scheme Eq. (3.21

). Matrix equations are

constructed in extensive

form as discussed in Sec. 3.6

. Hence, the

contributions from Eq. (3.21

) to matrix coefficients

and source vector

and source vector  are scaled by cell volume

are scaled by cell volume  , i.e.

, i.e.  and

and  , respectively, as

illustrated below.

, respectively, as

illustrated below.

, is discretised by

Eq. (3.8

). It

pre-calculates the volumetric flux

, is discretised by

Eq. (3.8

). It

pre-calculates the volumetric flux  , using

, using  interpolated by

Eq. (3.3

) with linear weights

Eq. (3.4

).

interpolated by

Eq. (3.3

) with linear weights

Eq. (3.4

).

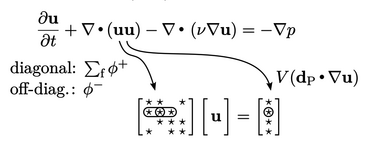

The transported  might be discretised

using the linear upwind scheme described in Sec. 3.14

. The scheme first applies

upwind discretisation, which contributes outgoing positive fluxes

might be discretised

using the linear upwind scheme described in Sec. 3.14

. The scheme first applies

upwind discretisation, which contributes outgoing positive fluxes

to

diagonal coefficients and negative fluxes

to

diagonal coefficients and negative fluxes  to off-diagonals. It

then adds an explicit contribution based on an extrapolated

gradient

to off-diagonals. It

then adds an explicit contribution based on an extrapolated

gradient  (see Sec. 3.14

). The gradient

(see Sec. 3.14

). The gradient

is

usually calculated by Eq. (3.18

) with gradient

limiting from Sec. 3.16

.

is

usually calculated by Eq. (3.18

) with gradient

limiting from Sec. 3.16

.

, is discretised by

Eq. (3.2

). It requires

, is discretised by

Eq. (3.2

). It requires

,

which is linearly interpolated from the cell centres. If the

surface normal gradient

,

which is linearly interpolated from the cell centres. If the

surface normal gradient  includes a non-orthogonal correction

includes a non-orthogonal correction

,

see Sec. 3.8

, then the term contributes to

,

see Sec. 3.8

, then the term contributes to

and

and  , as shown below.

, as shown below.

is calculated using Eq. (3.18

). Like all the

other terms described here, it is implemented in extensive form,

scaling by

is calculated using Eq. (3.18

). Like all the

other terms described here, it is implemented in extensive form,

scaling by  , so is calculated for each cell by the vector

, so is calculated for each cell by the vector

.

The relevant component (

.

The relevant component ( ,

,  ,

,  ) of this vector is then applied to the

respective equation for

) of this vector is then applied to the

respective equation for  ,

,  and

and  .

.