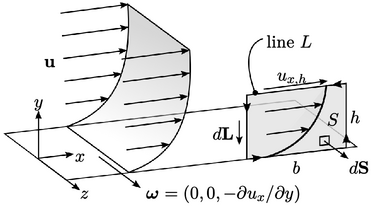

6.4 Boundary layers

Boundary layers4 are

regions of fluid formed along solid boundaries in which the velocity

varies: from zero at the boundary (no-slip condition,

Sec. 4.4

); to a value largely unaffected

by the proximity of the boundary, determined by the flow

conditions.

varies: from zero at the boundary (no-slip condition,

Sec. 4.4

); to a value largely unaffected

by the proximity of the boundary, determined by the flow

conditions.

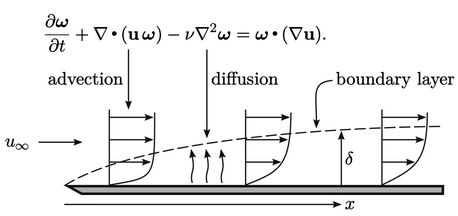

The figure above shows a boundary layer for flow

in the  -direction at speed

-direction at speed  , along a flat solid boundary oriented in the

, along a flat solid boundary oriented in the

-normal direction. At the boundary surface, the vorticity

-normal direction. At the boundary surface, the vorticity

is

significant.

is

significant.

Vorticity can be shown over a planar section of

the boundary layer of width  and height

and height

(above, right). Applying Stokes’s theorem, Eq. (2.39

), the integral =

(above, right). Applying Stokes’s theorem, Eq. (2.39

), the integral =

along the upper line (with zero along the wall and the verticals

sides). The average vorticity over plane area

along the upper line (with zero along the wall and the verticals

sides). The average vorticity over plane area  is therefore

is therefore

.

.

Boundary layers are the main source of vorticity

for turbulence. Turbulence occurs when instabilities, e.g. induced by roughness of the

boundary surface, cause the vorticity to become chaotic, sustained

by a sufficiently high  .

.

The growth of boundary layers is related to

vorticity transport. For flow over a flat plate, vorticity generated

at the leading edge is advected by the flow, while diffusing away

from the plate.

in time

in time  , see

Sec. 2.22

. In that time, it is advected

a distance

, see

Sec. 2.22

. In that time, it is advected

a distance  , where

, where  is the freestream flow speed. Comparing the

distances over the same

is the freestream flow speed. Comparing the

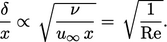

distances over the same  , the boundary layer thickness is

, the boundary layer thickness is

|

(6.6) |

is suitable for laminar boundary layers, with coefficient

is suitable for laminar boundary layers, with coefficient

depending on the definition of

depending on the definition of  . Data and analysis,

including e.g. the Blasius

solution5,

indicate

. Data and analysis,

including e.g. the Blasius

solution5,

indicate  in the case of the “99% thickness”, i.e. the distance from the wall where

velocity reaches 99% of its asymptotic value.

in the case of the “99% thickness”, i.e. the distance from the wall where

velocity reaches 99% of its asymptotic value.

In turbulent boundary layers, the diffusion

front advances more rapidly due to mixing, see Sec. 6.11

. As a result,

is

relatively insensitive to

is

relatively insensitive to  , e.g. the analytical solution

, e.g. the analytical solution

,

based on a one-seventh (

,

based on a one-seventh ( ) power law for the velocity profile.

) power law for the velocity profile.