6.5 Boundary layer separation

Boundary layers provide the main source of vorticity for turbulence as discussed in Sec. 6.4 . A boundary layer breaks away from the boundary when it reaches the end of the surface or by separation before reaching the end. Vorticity and turbulence are thereby swept into regions of fluid away from solid boundaries.

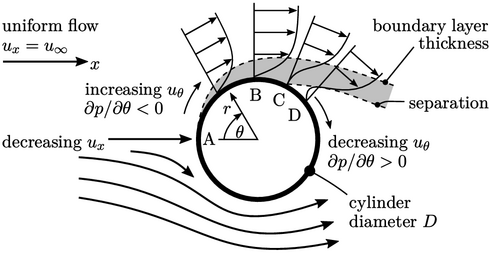

Flow around a cylinder illustrates boundary layer

separation, vorticity and turbulence. The fluid flows at uniform

velocity  upstream of the cylinder. It decelerates to stagnation,

upstream of the cylinder. It decelerates to stagnation,  , at point A on the

surface (in the

, at point A on the

surface (in the  -normal direction).

-normal direction).

High pressure at A introduces a favourable pressure gradient

which

increases the flow speed

which

increases the flow speed  around the cylinder towards B, developing a

boundary layer in the process.

around the cylinder towards B, developing a

boundary layer in the process.

The flow reaches a peak speed at B, then

decelerates over the downstream side of the cylinder. The

adverse pressure gradient

causes

causes

to

decrease. At some point C, the velocity gradient can reach

to

decrease. At some point C, the velocity gradient can reach

.

Beyond C, the boundary layer can separate such that

.

Beyond C, the boundary layer can separate such that  along its profile, see

point D.

along its profile, see

point D.

Boundary layer separation in a cylinder depends

on Reynolds number  , Eq. (2.68

), using

, Eq. (2.68

), using

and

and  . For

. For  , there is no separation, with the flow exhibiting a

pattern downstream that mirrors the upstream flow.6

, there is no separation, with the flow exhibiting a

pattern downstream that mirrors the upstream flow.6

For  , the boundary layer separates with its

vorticity sustaining a pair of vortices attached to the rear of the

cylinder.

, the boundary layer separates with its

vorticity sustaining a pair of vortices attached to the rear of the

cylinder.

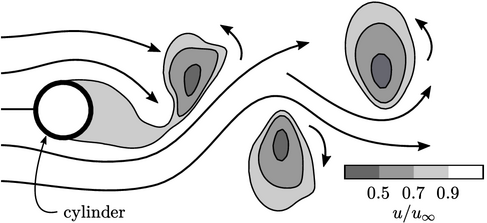

At  , vorticity is released downstream as vortices

break off from the cylinder in a periodic manner known as the

Kármán

vortex street, shown above.

, vorticity is released downstream as vortices

break off from the cylinder in a periodic manner known as the

Kármán

vortex street, shown above.

At  , the vorticity starts to become become chaotic,

with turbulence beginning to appear in the vortices. At

, the vorticity starts to become become chaotic,

with turbulence beginning to appear in the vortices. At

,

the entire wake region becomes turbulent.

,

the entire wake region becomes turbulent.

The frequency of vortex shedding is characterised

by another dimensionless number from Eq. (2.68

), the Strouhal

number  . For

. For  , experiments show7

, experiments show7  , where

, where  is the period at which the vortex pattern

repeats.

is the period at which the vortex pattern

repeats.