7.4 Turbulent boundary layers

At solid walls, the tangential flow speed

increases rapidly across a thin boundary layer, as discussed in

Sec. 6.4

. At high

increases rapidly across a thin boundary layer, as discussed in

Sec. 6.4

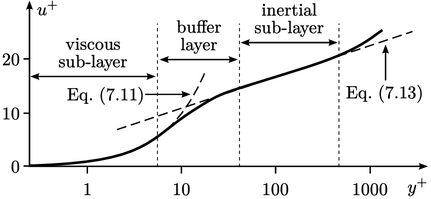

. At high  , the velocity

profile has a universal character shown below.

, the velocity

profile has a universal character shown below.

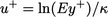

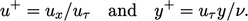

The profile compares measured data in

terms of a dimensionless velocity  and distance to the

wall

and distance to the

wall  , given by

, given by

|

(7.9) |

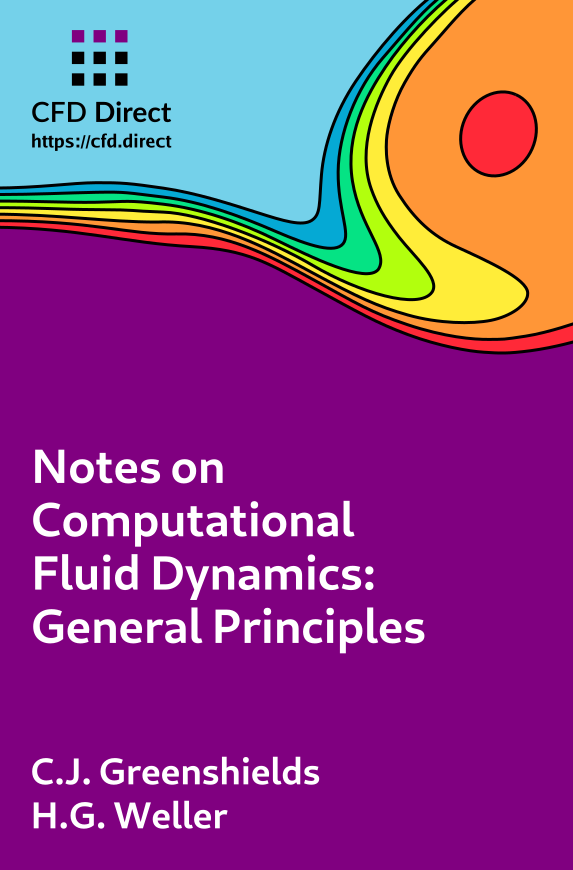

Both parameters in Eq. (

7.9

) are based on a

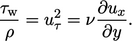

friction velocity

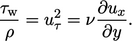

which is related to

the wall shear stress

by

|

(7.10) |

At the wall

. Close to the wall,

is suppressed,

creating a region where flow is laminar

, known as the

viscous sub-layer . The profile in this

region is described by the relation

|

(7.11) |

Turbulence becomes significant through the

buffer layer which describes the

region

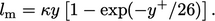

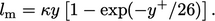

. Van Driest provides a model for the increase in mixing

length through this region, by

|

(7.12) |

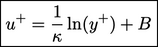

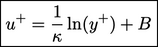

Finally, in the

inertial

sub-layer

for

, flow is turbulent and the velocity profile is described by

the

logarithmic law of the

wall, often abbreviated to simply the

log law, according to

|

(7.13) |

The equation includes Kármán’s constant

and constant

.

For a smooth wall,

– 5.5 is commonly used. Both

Eq. (

7.11

) and Eq. (

7.13) can

be derived assuming a constant shear stress across the profile,

equating to

at the wall. In the viscous sub-layer, the shear

stress is laminar, so

|

(7.14) |

This equation integrates with a zero constant of integration to

give

, from which Eq. (

7.11

) is derived. In the inertial

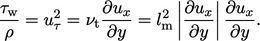

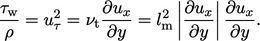

sub-layer, the shear stress is turbulent (laminar is negligible),

so

|

(7.15) |

Assuming

gives

, which integrates to yield Eq. (

7.13). In

the inertial sub-layer,

as described in Eq. (

7.5

), which combines with

Eq. (

7.15

) and Eq. (

6.31

) to give

|

(7.16) |

increases rapidly across a thin boundary layer, as discussed in

Sec. 6.4

. At high

increases rapidly across a thin boundary layer, as discussed in

Sec. 6.4

. At high  , the velocity

profile has a universal character shown below.

, the velocity

profile has a universal character shown below.

and distance to the

wall

and distance to the

wall  , given by

, given by

which is related to

the wall shear stress

which is related to

the wall shear stress  by

by

. Close to the wall,

. Close to the wall,  is suppressed,

creating a region where flow is laminar

is suppressed,

creating a region where flow is laminar  , known as the

viscous sub-layer . The profile in this

region is described by the relation

, known as the

viscous sub-layer . The profile in this

region is described by the relation

. Van Driest provides a model for the increase in mixing

length through this region, by6

. Van Driest provides a model for the increase in mixing

length through this region, by6

, flow is turbulent and the velocity profile is described by

the logarithmic law of the

wall, often abbreviated to simply the log law, according to7

, flow is turbulent and the velocity profile is described by

the logarithmic law of the

wall, often abbreviated to simply the log law, according to7

and constant

and constant

.

For a smooth wall,

.

For a smooth wall,  8 – 5.5 is commonly used. Both

Eq. (7.11

) and Eq. (7.13) can

be derived assuming a constant shear stress across the profile,

equating to

8 – 5.5 is commonly used. Both

Eq. (7.11

) and Eq. (7.13) can

be derived assuming a constant shear stress across the profile,

equating to  at the wall. In the viscous sub-layer, the shear

stress is laminar, so

at the wall. In the viscous sub-layer, the shear

stress is laminar, so

, from which Eq. (7.11

) is derived. In the inertial

sub-layer, the shear stress is turbulent (laminar is negligible),

so

, from which Eq. (7.11

) is derived. In the inertial

sub-layer, the shear stress is turbulent (laminar is negligible),

so

gives

gives  , which integrates to yield Eq. (7.13). In

the inertial sub-layer,

, which integrates to yield Eq. (7.13). In

the inertial sub-layer,  as described in Eq. (7.5

), which combines with

Eq. (7.15

) and Eq. (6.31

) to give

as described in Eq. (7.5

), which combines with

Eq. (7.15

) and Eq. (6.31

) to give